Chris Haw - Building on the legacy

Chris Haw: Orthopaedic surgeon at Footscray Hospital 1978–present

Mr Haw was head of the orthopaedic unit for about 25 years. He is a recipient of a lifetime achievement award from the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons for his services to the community of the western suburbs.

The unit has grown to become the biggest orthopaedic unit among Victoria’s hospitals, with 21 surgeons on staff.

It has a reputation for excellence in research, for its training program and its innovative auditing program. The auditing program, created by the unit’s current head, Mr Phong Tran, has been adopted by the Australian Orthopaedic Association and by Western Health in other areas of its hospital services.

Mr Haw was the Footscray Football Club’s orthopaedic surgeon for several years in the mid 1980s, after one of his colleagues, the obstetrician and gynaecologist George Thoms, a staunch Bulldogs supporter, encouraged him to get involved in the club.

Memories of the early days

“In the 70s the orthopaedic unit was in a small ward. We used to look after all age groups, including babies. We had them up in gallows traction in the cots reducing dislocated hips, doing open surgery on babies’ hips.

A lot of patients were still treated in traction systems and would sometimes spend months in the hospital.

When I first started you were on call for a full month at a time. So I was often operating in the middle of the night on patients who had fractured necks of femurs and multiple fractures because they’d been in serious road accidents.

We were taking serious trauma cases then. It was the era before the late 1980s, before the level 1 trauma centres at the Alfred and Royal Melbourne Hospitals were developed.”

Trauma

“We used to get some horrendous cases in the emergency department, where people had severely macerated limbs and amputations were not uncommon. When people had desperately mangled limbs we amputated them. It meant we were able to get people rehabilitated much quicker than if we had tried to salvage the limb.

At that time I was able to make the decision to amputate unilaterally and tell the patient that the limb wasn’t salvageable.

Later on you couldn’t do that because of medico-legal implications. Now you need a second surgeon to support your decision.

Unfortunately now, in the majority of cases, limbs are salvaged that should not be. There’s a general tendency to try and save the limb because of pressures brought to bear on surgeons from patients’ expectations that limbs can be saved.

Some limbs can be saved. But in about 60 per cent of cases, there are real problems associated with trying to save limbs – chronic pain for the patient and their inability to get back into the workforce. They lose their jobs and have no means of getting an income.

I work on medical panels and I see the huge amount of time these patients spend in rehabilitation. Then often two years down the track, the limb is subsequently amputated, by which time the patient’s whole life has been ruined.

There are huge advances in prosethetics now. If I had a mangled limb – a three B or C fracture of my tibea – I wouldn’t hesitate to have a below knee amputation.”

Memorable characters in surgery

“Danny Gillespie was the head orderly and union rep for the Health Services Union in the 1980s and 1990s. He was quite a character and ruled the place – you couldn’t function without having Danny on side. The hospital couldn’t function either because in those days the union was very powerful.

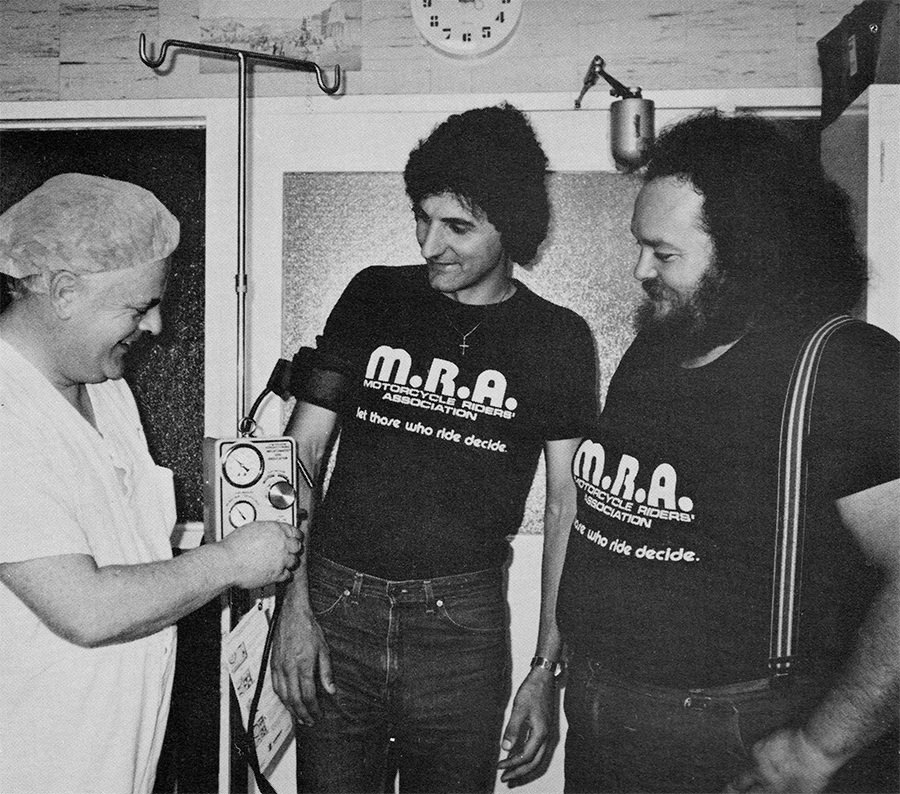

Theatre technician Danny Gillespie shows John Kalevitch and Lance McDiarmid from the Western Region Motorcycle Riders’ Association the new equipment for which the MRA raised money. The special tourniquet gives the operator fine control over the patient’s blood flow to an area before or during an operation, and keeps blood loss to a minimum.

Western Health archives

If there was an issue that the hospital was trying to pursue and Danny didn’t like, without hesitation all staff could be withdrawn. He must have been a thorn in the medical director, Mary Stannard’s side.

For some reason he liked the orthopaedics unit and he was always manufacturing things. We had a workshop at the hospital where we could have tools made for surgery when we wanted to do special things. I designed several tools for surgery and Danny helped with that.

He developed what we called the ‘Gillespie Pillow’ for me, which I used for my spinal operations. It was a wedge-shaped pillow with an opening for the patient’s abdomen. So when the patient was prone the pillow made it safer for the patient during surgery by reducing the pressure on the main veins returning to the patient’s heart.”

Moving out from the Royal Melbourne’s shadow

“The surgical staff wanted to be independent from the Royal Melbourne when the Department of Surgery was set up in 1993. We didn’t like the idea that some of the hospital’s administration was taking place through the Royal Melbourne.

We thought that was totally inappropriate. We didn’t like the structure. We thought we were able to provide a really good teaching program and we didn’t require the Royal Melbourne’s involvement. There was pride in being a member of the Western and a tremendous joie de vivre.”