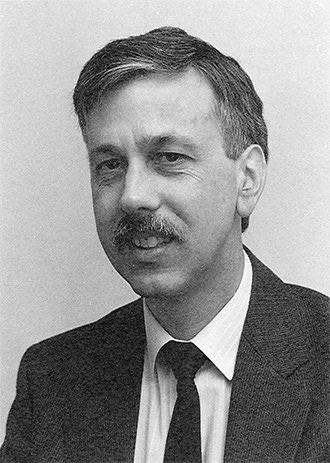

The first group of medical students at Footscray Hospital arrived in 1964, brought there by Vernon Marshall, one of the hospital’s small team of honorary general surgeons.

Professor Marshall combined his duties at Footscray with surgical work at two of Melbourne’s big teaching hospitals - the Royal Melbourne and Prince Henry’s.

At the Royal Melbourne he was a Melbourne University appointee, employed by the university to teach its medical students and conduct surgery at the hospital’s Department of Surgery.

Professor Marshall’s appointment as an honorary surgeon at Footscray in 1963 enabled the university to extend its undergraduate medical training program beyond the big city hospitals.

That year President Roy Parsons and the Footscray Hospital board met with Professor (Sir) Sydney Sunderland, Dean of Melbourne University’s Faculty of Medicine, to discuss the idea of Footscray helping to train some students from the university’s clinical school at the Royal Melbourne.

The following year Footscray Hospital’s honorary medical staff began conducting Saturday morning seminars at the hospital for final year medical students from the Royal Melbourne.

Professor Marshall said the first batch of students to arrive at Footscray had an invigorating effect on the hospital. “The ethos of a hospital is vastly improved by having a young, ragamuffin body of students asking questions.”

The teaching program gradually expanded. Medical students were attached to a single ward for up to three months, shadowing the doctors and immersing themselves in the daily routine of patients and staff.

“Good teaching is about stimulation rather than recitation. It was patient based teaching rather than lecture-based,” Professor Marshall said. “You’re immediately confronting real patients and you follow that patient through the evolution of that illness through to surgery through to the cure of the disease and recovery. That’s a very striking illustration of the natural history of an illness - a great contribution that surgery can make to the evolution of disease.”

Over the next eight years the hospital continued to receive a limited number of medical students from Melbourne University for experience in its casualty and outpatients departments as well as medical students from Monash University for tuition in obstetrics.

It established strong inter-hospital relationships with three big teaching hospitals - the Royal Melbourne, St Vincent’s and Prince Henry’s Hospitals. Each provided medical staff at registrar and junior resident level on a rotation basis to Footscray. “Without their assistance it would have been most difficult to have adequately staffed the hospital in certain areas,” President Parsons said in the 1972 annual report.