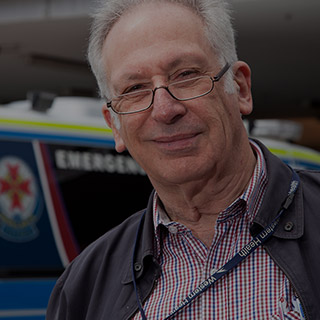

Kevin King

Orthopaedic surgeon at Footscray Hospital 1964–1985

Born in 1933 in St Kilda, Mr King grew up in Kew and was educated at Xavier College. He graduated from Melbourne University’s medical school. His father, Thomas, was a legendary orthopaedic surgeon believed to have established Melbourne’s first orthopaedic unit at St Vincent’s Hospital.

Kevin King arrived at Footscray in 1964 as an honorary surgeon. He was the first head of the hospital’s orthopaedic unit.

The honorary era – rites of passage for young surgeons

“I was brought up in an era where your major responsibility was to the public system because it was where you were taught and it was where you made your reputation. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, if you didn’t have a public hospital job, GPs didn’t know you and you didn’t get any private practice.

In those days, in the 60s, private practice was a very small section of your practice, about one third. At Footscray the Board allowed us to have 20 per cent private patients and 80 per cent public.

People tend to forget that modern medicine is only 150 years old and before that it was a bloodbath. It was always strapped for money.”

A tribal, sectarian culture

“Up to the early 1960s, there were only four major teaching hospitals in Melbourne: the Alfred, St Vincent’s, the Royal Melbourne and Prince Henry’s.

From medical school you had to be in the top quartile of your final year to be appointed to a junior residency position in a public teaching hospital. Then to be re-appointed you had to have done well in your first year.

It was very tribal, very sectarian, very segregated. From medical school all the WASPS went to the (Royal) Melbourne, all of the Catholics went to St Vincent’s and the rest went to the Alfred, including the Jews. That’s the way society was then. It wasn’t good but it produced a great product and tremendous camaraderie.

The tribalism eventually broke down. For example I was the first person ever to be appointed head of surgical unit at the Royal Melbourne from outside the RMH. I was just on the crest of the wave of change.

St Vincent’s was my old hospital. All residents had to live in in the first year. It was a monastic existence, we all turned into boozers. Every junior resident had to be in his room by midnight and the females as well because you were then on call from midnight. In the ‘60s you knew everybody because you lived with them, you worked on the same patients all the time, you worked with the same ward sisters.

You could not get a job as a first or second year resident, which was vital for future training, if you were married. You had to be single.”

No money, no training programs in surgery

“It was a custom. It was a strange sort of renaissance style of doing things. Each hospital was like a medieval city in its own right, all competing against one another. It was a healthy rivalry but a totally different system compared with today’s training system.

Up until the 1960s you had to get in the top quarter of your final university year to get a job at your teaching hospital and you had to do two years of residency. Then if you wished to specialise you had to bugger off and spend five years as a surgical registrar in England or, to some extent, in America.

Not many wanted to do that because there wasn’t any money in surgery in those days. So those who did want to go on to England for five years to train to become a specialist were a very motivated lot.”

The English training ground

“It was a great experience. The National Health Service was a great system.

You had to get a surgical qualification either the M.S. or the F.R.C.S. Then that merged into the F.R.A.C.S - a world ranking qualification.

In England you were on call 24 hours a day, it was really exploited labour but it was great fun. You were badly paid, but you were learning hand over fist, taking enormous responsibility.

As residents in the UK, we all did hundreds of hours of operations of a wide and complex nature, but always supervised by experienced senior registrars, who were the real sufferers in the English system. They hung around like indentured labour, like grizzled old veterans of the Napoleonic wars. They couldn’t get consultants jobs but they were incredibly experienced.

I arrived back from England in 1964 because my father had fallen ill and had to give up his practice. In those days you had to get a public hospital job because that was the only way you could get private patients referred to you – you could make a living and be recognised by your peers. Unless you were taken seriously by your colleagues, you were not recognised as a specialist because they didn’t have training programs in those days.

Over the next five years I worked at three hospitals in honorary positions as a consultant. We used to do five to six public operating sessions each week. We all did an enormous amount of operating.

The Australian system was based on the English system. You were thrown in at the deep end. By the time we (surgeons) came back from England we were pretty well competent and then we went on to do enormous numbers of hours – Kendall Francis and all of these chaps – we were always on call day and night. It was great fun but it was also invaluable experience.”

The unique appeal of Footscray Hospital

“A job came up at Footscray to replace Kingsley Mills, an orthopaedic surgeon at the hospital. I walked into a busy, middle level hospital that was big enough to have everything in it, but small enough to exert influence. Everybody knew what everybody else was up to.

I eventually ended up in a large pool at the Royal Melbourne, as director of orthopaedic surgery, because I learnt my trade at Footscray. Footscray was a working class area of Anglo Celts and new Australians – Italians, Greeks and some Turks – basically salt of the earth families who’d been living there for years. There was a wide variety of disease and a wide variety of trauma. It was a hospital where you could actually get things done because you could go down and see the management and get things sorted out.

A crowded waiting room, Outpatients department.

Western Health archives

For two years I ran the unit by myself, I didn’t even have a registrar. But what I did have were a couple of senior hospital medical officers, who assisted me in surgery. I used to rapidly teach them to operate and I did that right up until I retired.

I was sometimes accused of giving registrars too much responsibility but as long as I was in the room next door I gave them the same responsibility that I’d been given because you don’t learn otherwise.

The Western (Footscray) was the best hospital I ever worked at because of the camaraderie. The patients were great. The equipment wasn’t expensive in those days . . . you could just get on with the work and there was a lot of work to be done.

It was efficient and it had first class surgical staff, people like Kendall Francis. At the Western you were dealing with equals, from the orderlies to the ward staff, to the surgeons.”

The shark pool

“I ended up as chairman of the senior medical staff for a couple of years, working with Trevor Jones. There were all these chaps like Kendall making themselves as difficult as they could be but essentially reasonable. But there was no way you could put anything over that lot. It was a medium sized pool full of extremely ferocious sharks.

Everybody was wary of Kendall. He was an absolute charmer but as tough as old boots. You’d never get the better of Kendall. All you could do was fight him off to a standstill . . . I used to do about three operating lists a week at the Western. I always made sure that my Friday morning list didn’t run into his afternoon.

Orthopaedics is the largest and busiest of all the surgery specialties. In any public teaching hospital between 20-25 per cent of all surgery done is orthopaedic. That’s why it’s like having an elephant in your front room . . . Orthopaedics is loathed by all other units because it just keeps expanding.

About 50 per cent of our work was trauma, from minor to major trauma and the rest was arthritic disease.”

Vietnam war

I worked in Vietnam in 1966 with a civilian surgical team. War trauma is no more severe than road trauma. If you get hit by a five-tonne truck or you get blown up by a carpet bomb, the effects are usually the same.

People, like Kendall Francis and the rest went off to Vietnam in civilian surgical teams too. The Royal Melbourne, the Alfred, Prince Henry’s and Footscray used to send the surgeons and physicians. We were in a rural area and treated mainly the civilian population.

Vietnam was awash with polio so we treated polio and all the other diseases that people would get as well as war injuries. In Vietnam I found that I was doing exactly the same work as I had been doing in Melbourne, except multiplied by a factor of five.”