The first university chair of surgery was established at the hospital in 1993 when Bob Thomas was appointed as a professor and given the task of setting up a Department of Surgery affiliated to Melbourne University.

Before taking on the job, Professor Thomas was a surgeon at the Royal Melbourne and Epworth Hospitals, while also working as a cancer researcher in Melbourne University’s department of surgery at the Royal Melbourne.

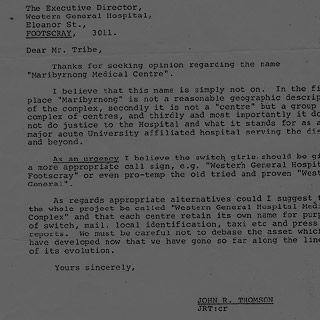

Professor Bob Thomas, the hospital’s first professor of surgery.

David Johns

He said Vernon Marshall, then Professor of Surgery at Monash University and Professor David Penington, Melbourne University’s Vice-Chancellor and former Dean of Medicine, were highly influential in persuading the Department of Health about the potential benefits of establishing university research departments in medicine and surgery at Footscray.

“There was a feeling among the decision-makers that as a general rule, if you have a research program going in a hospital you usually get better care and outcomes for patients, “ Professor Thomas said. For example if you have a group of patients in a clinical trial, they usually do better than patients who are not in a clinical trial.”

Research departments attracted surgeons who wanted to combine their clinical practice with research.

“You get a group of people who have an interest in life above and beyond their immediate clinical practice,” Professor Thomas said. “That’s good for the quality of care for the patients. It’s good for young trainees because their progress is often predicated on their research efforts as well as their clinical efforts.

“Incorporating young people into research projects acts as a cauldron for new ideas, for innovation.”