In the early 1960s, Joe Epstein was a young man starting his medical career. As a newly appointed junior resident medical officer at Footscray and District Hospital, he lived in a rundown terrace house in North Melbourne, renting rooms on the top floor.

The trip from home to work was short, a ten-minute drive in his old English open-topped Ford Anglia tourer across the Maribrynong River and into the western suburb of Footscray. The suburb was the heartland of Melbourne’s heavy agricultural industries. It teemed with abattoirs, tanneries, iron and steel foundries, chemical and fertiliser works, rope and twine makers, farm machinery and munitions factories and other manufacturers.

Footscray and its neighbouring suburbs were home to some of Australia’s most famous companies, many of which were founded in the nineteenth century by local industrialists - H.V.McKay’s Sunshine Harvester Works, William Angliss Meatworks, Kinnear’s Rope Works, Borthwick’s Abattoirs, the Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR), the Australian Woollen Mill Company, Commonwealth Fertilisers and the Colonial Ammunition Company.

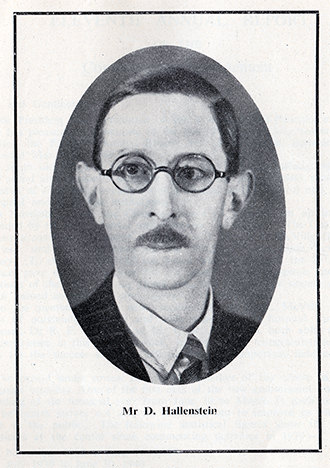

Mr D Hallenstein, of the Michaelis Hallenstein Company, was involved in the Hospital Movement since its inception. He served on the board of the Footscray Outpatients and Welfare Centre as vice-president and chairman of its finance committee until his death in 1949.

Western Health archives

One of the world’s biggest tanneries, Michaelis Hallenstein, sprawled across Hopkins Street and down to the riverside. Successive generations of local families toiled at the vast site from 1864 until it was demolished in 1987, producing glues, gelatine and leather products. The nearby William Angliss Imperial Freezing Works was the largest meatworks in the southern hemisphere at the start of the 20th century. When a young Joe Epstein was making his daily commute to Footscray Hospital in the 1960s and 70s, the meatworks and many of the area’s other huge industries were still operating.

“As you drove to work each day the environment was dominated by the smells from Michaelis Hallenstein, the smell of blood and animal processing,” said Mr Epstein, who is 74 and continues to work at the hospital. “You could hear the sounds of the animals. That old factory environment became part of my environment.”

The West’s industrial heydays began in the 1880s. At that time the Melbourne newspapers located on the eastern side of the Maribrynong, dubbed Footscray “Stinkopolis” because of the fumes and noxious waste belching from the suburb’s factories. For the citizens of Footscray the nickname was yet another piece of snobbery flung at their working class community from the other side of town. It fed the suburb’s nascent sense of itself as a self-reliant, frontier community. Footscray was powering Melbourne’s prosperity but it was underappreciated and neglected by the city’s establishment class.

That maverick, independent spirit helped shape Footscray’s struggle town culture. As early as 1889 it sparked the first stirrings of a grassroots citizens’ coalition that later evolved into the 1919 Hospital Movement, whose members then campaigned for decades to get a public hospital built in Footscray.

When the hospital eventually opened in 1953 many of its surgeons embodied the Hospital Movement’s maverick spirit. They were undaunted by working on ‘the wrong side of town’. This book tells the stories of these surgeons - Joe Epstein and his colleagues – who became role models for the next generation of Footscray surgeons because of their commitment to the hospital and the people of the West.