John Thomson was one of the first surgeons to work at the newly built Footscray and District Hospital.

He arrived in 1955 when the suburb was bristling with civic pride about two of its main public institutions – its new 205-bed hospital and the Footscray Football Club, which had triumphed the previous year over its richer, more highly fancied rivals to win its first premiership.

Footscray was the first large acute care general hospital to be established beyond Melbourne’s city’s centre and its inner suburbs.

Mr Thomson, born and raised in Brisbane’s working class suburb of Kangaroo Point, immediately felt at home. “The patients were great people, very down to earth. I came from a poor family and I worked my way up. I knew what it meant to suffer and to try hard.”

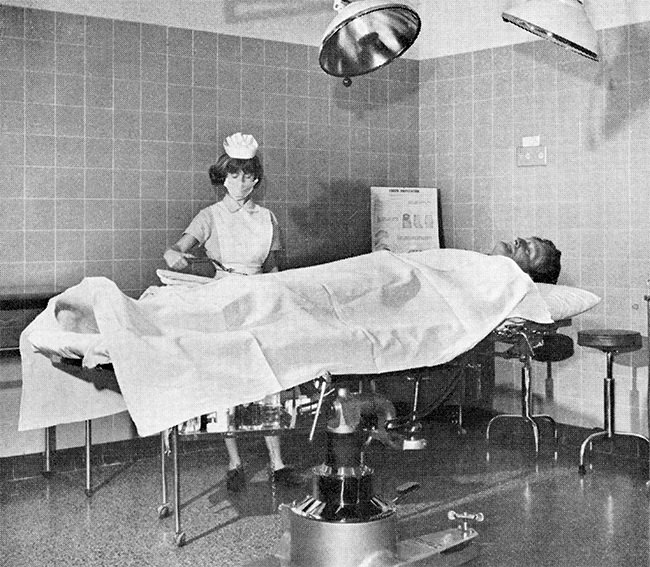

At the hospital he joined a small team of general and specialist surgeons working in unpaid, honorary positions. Each had a rostered day for operating on patients.

There were no specialist surgical departments. Instead all of the surgeons, including those with specialist expertise, were expected to deal with most of the surgical patients who came through the hospital’s doors, from people needing a simple procedure to those requiring complex emergency surgery.

“It was pretty primitive,” Mr Thomson said. “There was no running water on the top floor of outpatients so we had two trays of water to wash our hands in. There was a lack of instruments so we had to improvise and brought some of our own.”

Almost all surgeons in Australia worked in unpaid honorary positions at public hospitals until 1975 when the Whitlam government’s radical overhaul of the health system enabled public hospitals to directly employ surgeons.

Under the pre-1975 honorary system surgeons earned their incomes from treating private patients at private and public hospitals. Some were also employed by Melbourne or Monash University to do clinical work and teach medical students at one of the large city-based public teaching hospitals.

Honorary positions at public hospitals were highly prized by surgeons, despite the absence of payment for their services. The appointments gave surgeons access to general practitioners, enabling each surgeon to establish a pipeline of private patient referrals from GPs.

Most surgeons had honorary jobs at several hospitals.

“As honorary surgeons we had an understanding with the hospital’s staff and management to give service and to help people,” Mr Thomson said. “It was a gentleman’s arrangement to do a job between professionals and professional administrators. That meant we took short cuts. . .We’d say, ‘Look I’ve got such and such could you help me out?’…. There was endless cooperation.”

Mr Thomson operated once a week at Footscray and was also called out several times each week to treat emergency cases.

“I’d travel out to Footscray by car. It was quite a hairy trip because there were new road signs, new road developments all the way. But parking was wonderful in the ‘50s because there was nobody there.

Parking was easy at the hospital in 1957. The seven-storey nurses’ home, William Pridham House, is in the background.

Western Health archives

“The theatre lists were very long, much longer than the surgery lists at the Royal Melbourne where I worked, because the need was greater. It was a very poor district and people often suffered and put up with things.

“You felt the need, you felt it all over you. The amount of sickness that wasn’t being provided for was just incredible. I remember one woman had a huge tumour growing in her throat and she could hardly breathe. It was too far for her to go into Melbourne so I debulked the tumour. It was the best way to deal with it and give her life.”

Kendall Francis was another young recruit to Footscray’s surgical team. He also came from a working class family and had spent part of his childhood living in Eleanor Street, opposite the site of the future hospital.

Before his 1956 appointment to Footscray Hospital, Mr Francis served in Korea with the Australian Army’s Medical Corp.

“Footscray was considered by many of the chaps at that time as a stepping stone to get experience in surgery,” he said. “It was a great training ground because of the amount of work. We did the whole spectrum of abdominal surgery, neck and limb - mainly workplace accidents and trauma.”

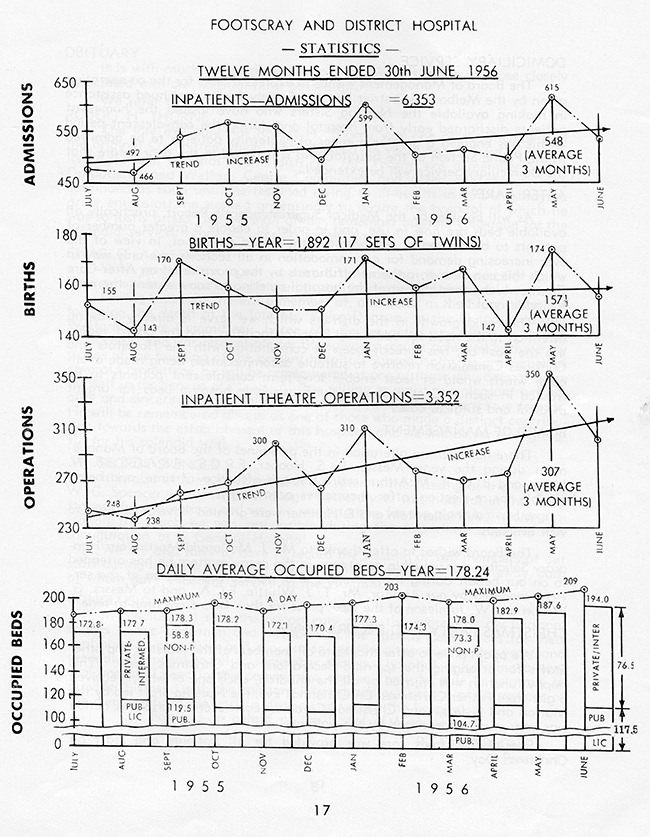

The new hospital at Eleanor Street catered for general medical and surgical patients and maternity patients. It had a children’s ward and a premature baby nursery. Its ancillary services included Casualty and Outpatients Departments, Pharmacy, Pathology, X-Ray, Physiotherapy and Almoner Departments.

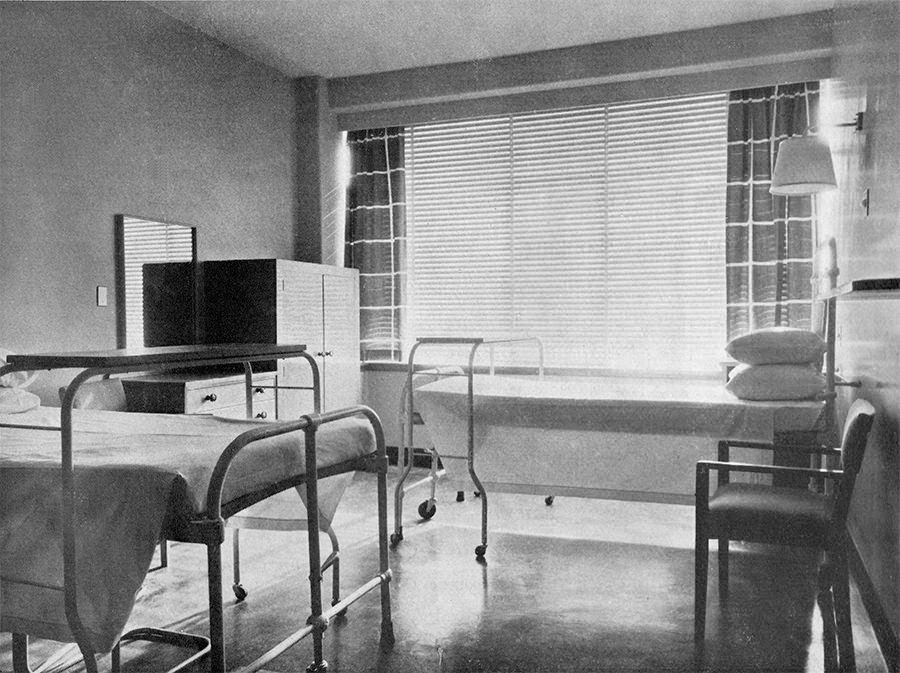

A hospital ward in 1953. The medical ward was on the first floor, surgical on the second, midwifery on the third, and children on the fourth floor.

Footscray Historical Society